Oak Treehopper

Obscure Bird Grasshopper

span worm

Long-Tailed Giant Ichneumonid Wasp

Two Striped Walking Stick

Saltmarsh Caterpillar

Hover Fly

Giant Leaf-footed Bug

Brazilian Skipper/Caterpillar

Brunner’s Mantis aka Northern Grass Mantis

June Bug

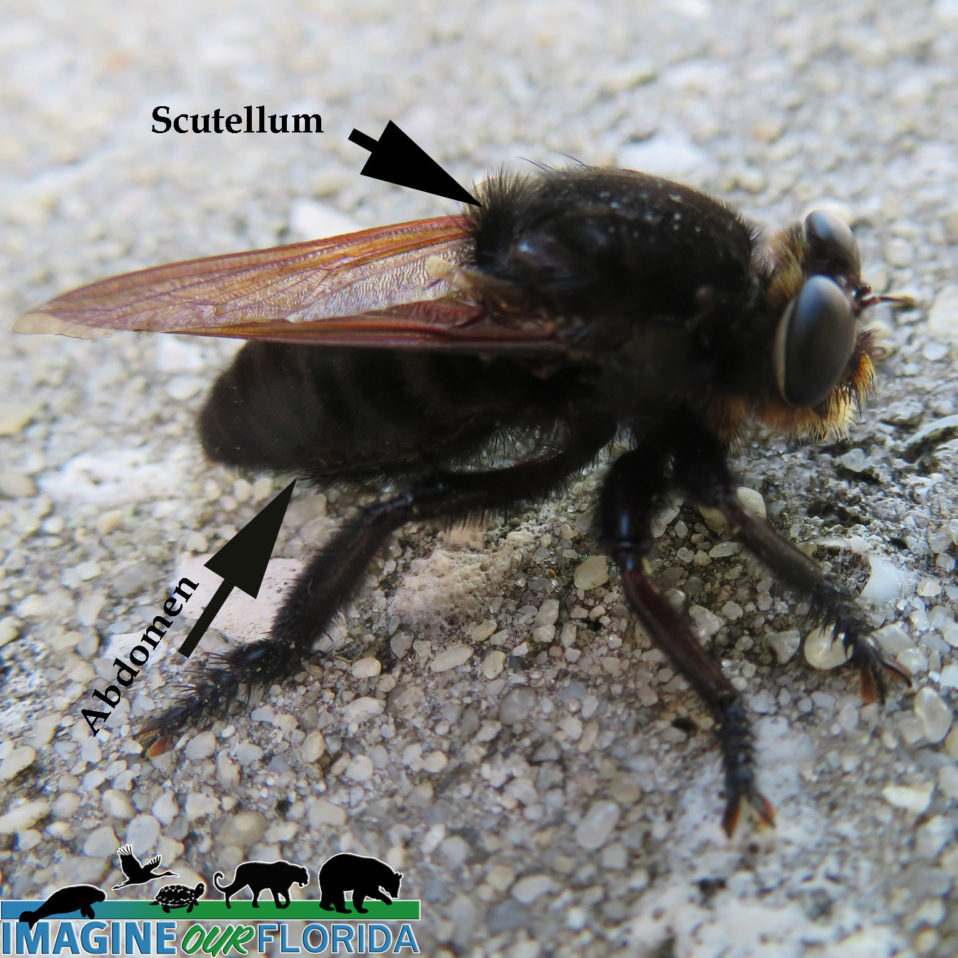

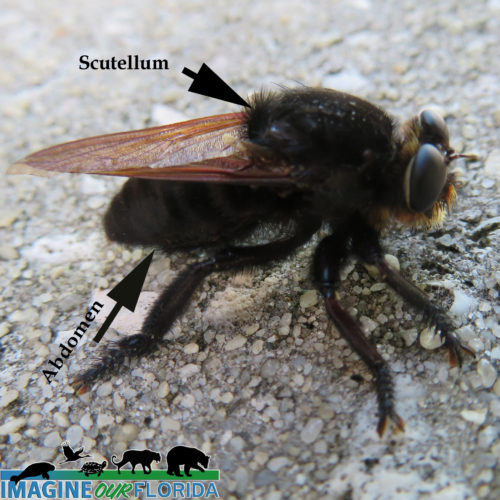

Black Bee Killer and Batesian Mimicry

Summer Fishfly

The Summer Fishfly, Chauliodes pectinicornis, is an insect that grows to approximately 1 1/2 inches. It is omnivorous and spends most of its life in still or slow-moving water with lots of detritus. Th fishfly undergoes a complete metamorphosis in a log or under bark and emerges as the adult you see here. It will mate, lay eggs near the water, and die within seven days.

Florida Harvester Ant

Ladybug

Dark Flower Scarab Beetle

Dark Flower Scarab Beetles (Euphoria sepulcralis) have white markings on a black or dark brown body that reflects a metallic bronze or green color in the sunlight. They are daytime flyers and can often be found snacking on flowers in yards throughout Florida.

“The adults feed on tree sap, a wide variety of ripening fruits, corn, and the flowers of apple, thistle, mock orange, milkweed, dogwood, sumac, yarrow, daisies, and goldenrod.” Ratcliffe (1991). Occasionally, these common beetles are considered pests because they love to munch on the flowers of fruit trees, roses, and corn.

Dark Flower Scarab Beetles make tasty dinners for a variety of animals. Grubs, which hatch underground from eggs, are eaten by birds, moles, and skunks. Other animals such as frogs, bats, and birds eat adult beetles.

Photo Credit: Aymee Laurain

Garden Flea Hopper

The Garden Flea Hoppers (Microtechnites bractatus) are tiny little insects that lay eggs in plants’ stems. After about 14 days, the eggs hatch, and little green nymphs emerge. As they grow, they turn black, and their wings expand. These small pests tend to damage soft stem plants such as this scarlet salvia (Salvia coccinea). Luckily, parasitoid wasps are effective at keeping these little bugs from causing too much damage. Other insects have been suspected of managing their populations, but there is not much research to determine their effectiveness.

Photo credit: Aymee Laurain

Katydid

Meet Katy! A Katydid (family Tettigoniidae), to be exact. Listen to her chirp, and you will hear “ka-ty-did.”

Katydids love to hang out on palmettos, scrub oaks, vine-covered undergrowth, and in damp areas. They are solitary and sedentary creatures. Their coloring provides a wonderful camouflage from predators and humans. The veins in their wings mimic the veins in leaves. This makes it easy to blend in with the tree or plant they are resting on. Katydids are tasty treats for birds, wasps, spiders, frogs, and bats.

Katydids are primarily leaf eaters and feast most often at the top of trees and bushes where there are fewer predators. They will dine on an occasional flower and other plant parts.

Katydids are related to grasshoppers and crickets. Like their cousins, Katydids have strong legs and jump when they feel threatened. They are poor flyers, but their wings allow them to glide safely from a high perch to a lower one.

You can find Katydid eggs attached to the underside of leaves. They resemble pumpkin seeds and are lined up in a row. Adult katydids have a lifespan of about 4 to 6 months. They can grow up to 4 inches long, and their antennas can be double the length of their body.

Katydids are nocturnal. The next time you go outside after dark, take a flashlight. How many Katydids can you find in your yard? When you spot one of these beautiful insects, be sure to say hi to Katy.

Eastern Grasshopper Lubber

The Eastern Grasshopper Lubber (Romalea guttata) is very distinctive in its coloration. They are yellow with black along the antenna, body, and abdomen. Their forewings, which are rose or pink in color, extend along the abdomen. The hind wings, which are rose in color, are short. They can grow as large as 3 inches and can be seen walking very slowly and clumsily along the ground. Lubbers cannot fly or jump, but they are very good at climbing.

The Grasshopper Lubber can be found in wet, damp environments but will lay its eggs in dry soil. The eggs are laid in the fall and begin hatching in the spring. The female will dig a hole with her abdomen and deposit 30-50 yellowish-brown eggs. They are laid neatly in rows called pods. She will produce 3-5 egg clusters and closes the hole with a frothy secretion. Nymphs wiggle through the froth and begin to eat. The male will guard the female during this time.

Nymphs have a completely different appearance from adults. They are black with yellow, orange, or red strips. They will have 5-6 molts to develop their coloration, wings, and antennae. The coloration of adults will vary throughout their lives as well, and they are often mistaken for different species. There is no diapause in the egg development, and they take just 200 days to develop depending on temperature. A month after the Grasshopper becomes an adult, they begin to lay their eggs.

Both females and males make noise by rubbing their front and hind wings together. When alarmed, they will secrete and spray a foul-smelling froth. This chemical discharge repels predators and is manufactured from their diet. The Grasshopper’s diet is so varied that it is difficult for predators to adapt to the toxin produced. Their bright color pattern is also a warning to predators that they are not good to eat. Birds and lizards avoid them, but parasites will infect nymphs from the tachinid fly. Loggerhead Shrikes will capture the Grasshopper and impale it on thorns or barbed wire. After 2 days, the toxins in the lubber’s body will deteriorate enough for the prey to be consumed.

Lubbers are long-lived, and both the adults and the nymphs can be found year-round in Florida. This Grasshopper occurs in such large numbers in Florida that it can cause damage to your landscape’s plants. Lubbers will bore holes throughout a plant regardless if they are vegetables, citrus, or ornamentals. If their numbers are large enough, they can decimate a plant.

Did you know:

Lubber is an old English word. It means a big, clumsy, stupid person, also known as a lout or lummox. In modern times, it is normally used only by seafarers, “landlubbers.”

Photo credit: Dan Kon

Hanging Thief Robber Fly

The Hanging Thief Robber Fly (Diogmites) is an ambush predator that catches prey by either catching it from the ground or by catching it while on a plant. Once they obtain their food, they will use two legs to hang from a leaf or stem and use the rest to maneuver the food as they consume their catch.

The Hanging Thief Robber Fly is a large fly that hangs from leaves and branches waiting for its favorite food, bees, dragonflies, and biting flies like horse flies to pass by. It then takes chase and captures its prey in flight. It takes its prey to a branch or leaf where it pierces its victim with its mouthparts and drinks its fluids.

In this photo, you can see the behavior that earned this fly its common name of Hanging Thieves.

The genus Diogmites consists of 26 species in the United States, with 12 of those living east of the Mississippi River.

Florida Woods Cockroach

The Florida Woods Cockroach (Eurycotis floridana) is more commonly known as the palmetto bug.

The roach measures 1 to 1 1/2 inches long to 1 inch wide. They are reddish-brown to black and do not have fully developed wings. They appear wingless but have short vestigial wings. These roaches are larger than other species, so they are easier to spot.

Florida woods cockroaches are usually found under palmetto leaves and decomposing matter. Contact with the bug may cause skin irritation as they secrete a chemical from a gland under their abdomen. This chemical secretion is used to ward off predators, and it stinks.

With or without fertilization, the Florida woods cockroach produces an egg case known as an ootheca. The egg cases contain an average of 20 to 24 eggs and will hatch after 50 days. Without fertilization, only about 60% of the eggs are viable, and those that hatch will not live to adulthood. The nymphs undergo 6 to 8 weeks of molts before becoming adults. They can live for over a year.

Florida woods cockroaches rarely enter the home since abundant food is found outdoors. They eat mold, moss, lichens, and other organic material found in dark, damp places. However, they are primarily a detritivore since their diet consists mainly of organic waste and dead plant matter such as bark and leaves, thus returning vital nutrients to the ecosystem.

They may not be the most loved bug in our state, but the Florida woods cockroach plays a crucial role in our ecosystem.

Connect. Respect. Coexist.

Lightning Bug

Let’s be a kid again with the Firefly/Lightning Bug!

Remember those nights of wandering outside in the spring and summer and being surrounded by amazing little flying strobe lights. They would come out at dusk and stay only for a few hours. We captured them in glass jars and looked in amazement as we tried to figure out how their lights worked.

Fireflies are a good indicator species for the health of an environment. Unfortunately, these little miracles of life are on the decline throughout the world because of overdevelopment, pesticide use, and yes, light pollution.

The best thing you can do to support fireflies is to stop using lawn chemicals and broad-spectrum pesticides. Firefly larvae eat other undesirable insects. They are nature’s natural pest control.

If you miss seeing these little buggers, you’ll be happy to know Central Florida’s firefly season is at the end of March and early April. In fact, Blue Springs State Park stays open a little past their usual closing time and has guided tours at this time so you can enjoy nature’s light show.

Red Velvet Ant

The Red Velvet Ant (Dasymutilla occidentalis) – the name is a bit misleading. These fuzzy little insects aren’t actually ants but rather wasps. The males have wings and can fly but are harmless. The females, however, can deliver a powerful and painful sting. Fortunately, they do not have wings and can easily be avoided. These differences in sexes are called sexual dimorphism.

These wasps create burrows in the ground that look like small holes. Chances are you have walked by the burrows without noticing.

Lovebug

The Lovebug (Plecia nearctica) is one species of insect that most everyone in Florida knows and can identify. But, do you know ABOUT this species? There is a lot of misinformation about this species. Additionally, apart from the “flights” that occur, most know nothing else about this species’ natural history.

Let’s start with the one huge myth about this species. they are NOT man-made insects created in a lab at the University of Florida. This is a pervasive myth that has circulated for decades. They are a non-native species in Florida. The first time they were documented in Florida was in 1947. They are found across the gulf coast and as far north as North Carolina.

In Florida, lovebugs can be found throughout the year. But, there are 2 big “flights” of lovebugs, when they occur in huge numbers across their range. As many already know, the first flight occurs in late spring in the months of April and May. The second flight occurs in late summer in the months of August and September.

The lovebug has some interesting reproduction behavior. When females emerge from the ground, they are met by swarms of males. The male will clasp a female in the air and the two will fall to the ground. When the males first connect with the female, the male and female are facing the same direction. Then, the male turns 180 degrees and remains that way for the duration of mating.

Large females lay an average of 350 eggs before they die. Adult lovebugs have a short lifespan with females living up to 7 days and males up to 5 days. The eggs hatch in 2 to 4 days. The larva feeds on decomposing vegetation in moist, grassy areas such as pastures. In this way, they are extremely helpful in converting decaying vegetative matter into organic matter.

The adults feed on the nectar of numerous species, particularly sweet clover, Brazilian pepper, and the goldenrod seen in these photos.

There are few predators of the adult stage of lovebug as their slightly acidic insides make them unpalatable. The larva is food for birds such as robins and quail as well as spiders, earwigs, and other insect predators.

They do not bite or sting, but they are considered a pest species. The huge flights often occur near roadways and interstates (think of all the moist grass of cow pastures and roadsides which is a wonderful home for larva). It also appears that the bugs are drawn to the exhaust of cars. It has been proposed that the chemicals in car exhaust, aldehydes, and formaldehyde, are similar to the chemicals released by decaying organic matter. This means that lovebugs think they are hovering over a great spot to lay their eggs. Older car paints used to be damaged by the acidic internal organs of the lovebug, however, they do not have the same effect on new cars. Lovebugs can be very difficult to remove from the fronts of cars after the bodies dry and can clog radiators.

Love Bug Season usually occurs during May and September. Love Bugs (Plecia nearctica), are not a genetic experiment. They are actually a small black fly, with a velvet-looking appearance and a red area on the back of the head.

Love Bugs were not created and released by the University of Florida to control mosquitos. They do not eat mosquitoes. They are nectar drinkers and pollinators. They feed on Brazilian Pepper, sweet clover, and goldenrod. Adult Love Bugs do not eat at all.

Love Bugs are an invasive species from South America and have been in Florida since the 1940s. They are attracted by car exhaust, lawnmowers, other engines, and heat. The white splat on your car is their eggs. Love Bugs do not bite, sting, or transmit diseases.

Love Bugs serve an important ecological role in Florida. Their larvae convert plant material into organic components which growing plants recycle for food. Love Bugs live between 3 to 4 days.

Female Love Bugs lay between 100 to 350 irregular-shaped, gray eggs on decaying topsoil material such as cut grass or thatch. Once the eggs hatch the larvae will live and feed in the organic material until they turn into a pupa. The larvae are gray with a darker head. They will stay in the larvae stage between 120 to 240 days depending on the season. They are in the pupa stage 7-9 days. Mating takes place right away once they emerge as adults. The male emerges first then waits for the female. Females fly into the swarming males. Once the adults copulate they will remain joined until the female is fertilized. The male stays attached to the female to prevent another male from fertilizing her. This takes 2-3 days, then the female detaches, lays her eggs, and dies.

Remember, if the University of Florida had created Love Bugs, they would be orange and blue, not black and red. : )

Photo Credit: Andy Waldo

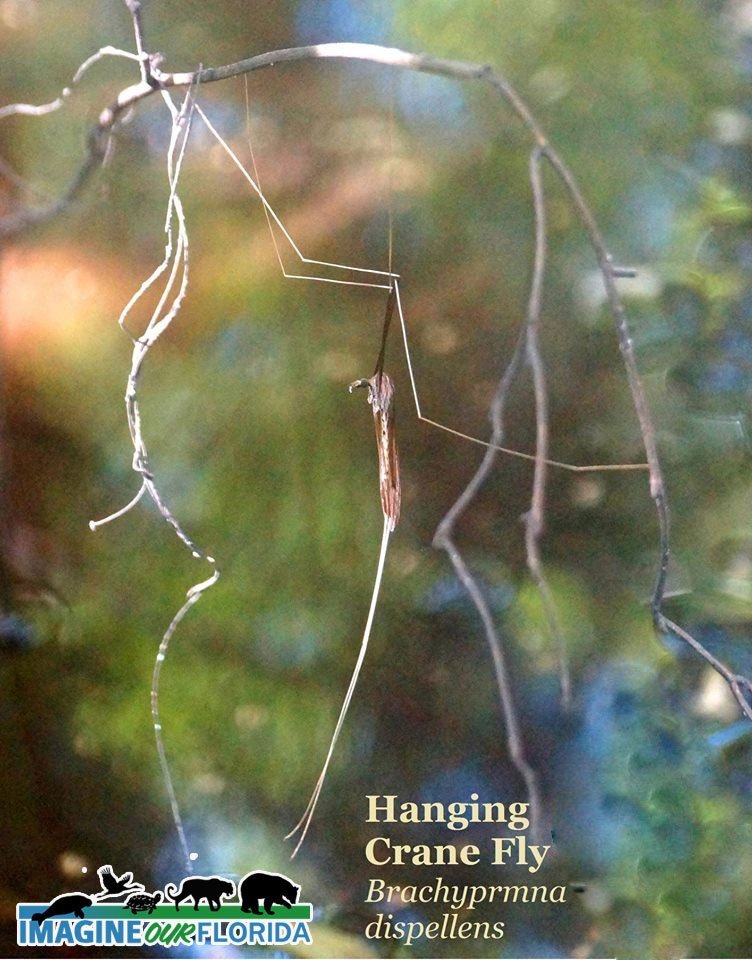

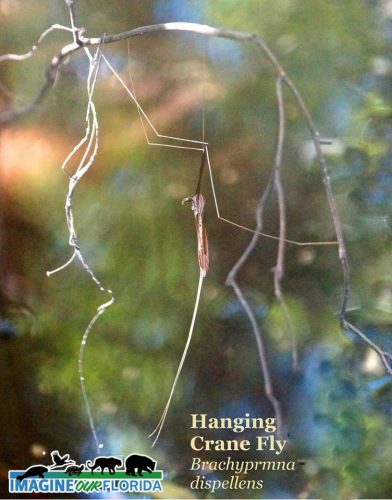

Hanging Crane Fly

Can you spot this stealthy insect? If you are out and about, you may miss them.

Like stick bugs, the Hanging Crane Fly (Brachyprmna dispellens) blends into its surroundings by pretending to be a hanging twig. This male hanging crane fly was observed performing a mating dance. This dance involves very quick shaking motions. Having more little hanging crane flies in this wet area of Alderman Ford park would be very beneficial since their diet consists of eating mosquitoes.

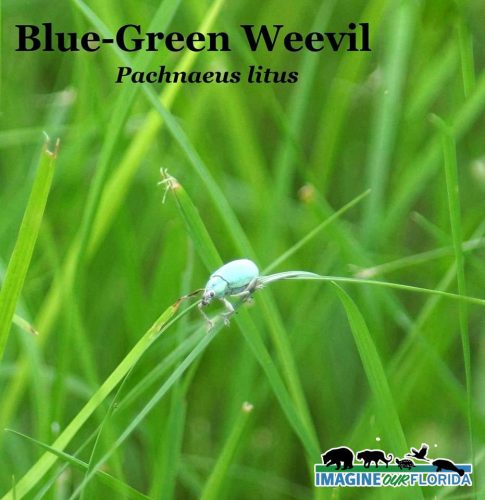

Blue-Green Weevil

Blue-Green Weevil (Pachnaeus litus).

These little bugs get a bad reputation, but such is the life of a weevil—the adults, such as this one, munch on plant leaves. The larvae fall to the ground and will munch on roots. This can be quite annoying in agriculture, especially citrus. For most plants, they aren’t much of a problem, but if they seem to get overwhelming, the USDA recommends the Trichogrammatidae family of wasps can help by preying on their eggs.

Black Soldier Fly

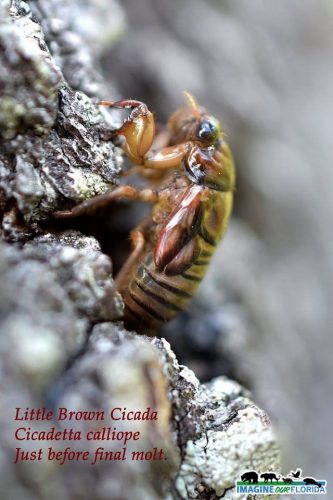

Little Brown Cicada

Cicadas are some pretty neat little creatures that are all around us but go largely unseen. They do not, however, go unheard. I bet, at some point, just about everyone has heard these guys screaming from the treetops at some point in their lives. But did you know that most of their lives are spent underground?

The species in the photos are of the Little Brown Cicada (Cicadetta calliope) or Grass Cicada. This is a small species of cicada, growing to just under 1 inch in size. Unlike its larger cousins to the north, this is not a periodical cicada. Those cicadas emerge every 13 to 17 years in numbers as great as 1.5 million per acre. For our residents who hail from the northeast, Florida has no periodical species. The closest location to observe the emergence of periodical species would be one of the 13-year varieties. Southeastern Louisiana will have its next emergence in 2027, and in central Alabama and Georgia, the next emergence will be in 2024.

So, some cool facts on these amazing insects. We all know their sound, but did you know only the males actually make noise. Cicadas make noise using timbals, a drum-like structure on either side of their abdomen. Only males possess this structure. They make different songs, calling songs to attract mates, protest songs when captured by a predator, and in some species, courtship calls, which are softer and made when the male is in visual or physical contact with the female.

The nymphs feed on the xylem sap from the roots of grasses and trees. This low nutrient sap is partially the reason for their long duration as a nymph. The minimum time a cicada spends as a nymph is 4 years but, in the case of the periodical cicada species, can be as long as 17 years.

Every cicada species molts 4 times as a nymph. For its fifth molt, the nymph emerges from the ground and molts into its adult form.

Cicadas do little to no harm to plants. They are harmless to food crops and landscape plants. They do not bite or sting and are an important food source for wildlife.

Watch our video here: https://youtu.be/be80lm4fn7k

Mosquito

The most common Mosquito in Florida is the Aedes aegypti species. The females are carriers of West Nile Virus, Eastern Equine Encephalitis, Dengue fever, Chikungunya, and Zika virus. Female mosquitos need blood to produce eggs. Therefore they love to live where people and pets are abundant.

You might be surprised to hear that 80 species of mosquitos call Florida home. This means that Florida has more mosquito species than any other state in the country. Of those eighty species, only 33 bother people and pets. We can narrow it further than that, 13 make people sick.

Some species are only located in certain areas of the state and others throughout the state. Mosquitos can spread a host of diseases from yellow fever, Zika, dengue, encephalitis. In your pets, they can spread heartworm and equine encephalitis. You can’t really avoid mosquitos as some feed during the day and others at night. You will run into one or the other eventually. In Southern Florida, mosquito season begins as early as February and continues through most of the year. In Northern Florida, mosquito season starts in March and follows a similar pattern. The warmer it is, the more active mosquitoes will be, especially at dusk and dawn. Permanent water mosquitos are attracted to standing pools of water, which they need for their eggs to hatch. Females will lay their eggs on the water surface, and the eggs will typically hatch in about 24 hours. Water is necessary to complete the life cycle, and soon the larva will change into a pupa and then emerge into an adult hungry for blood. Florida permanent water mosquito species include Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Culex quinquefasciatus, and Mansonia dyari. Make sure your house and yard are free of standing pools in flowerpots, buckets, and containers. Cut back overgrown yards. Lush plant life can be beautiful, but it’s also a mosquito magnet. They love resting in dense vegetation that can keep them warm and moist. Floodwater mosquitos lay their eggs in moist soil, not standing water. One female floodwater mosquito has the potential to lay 200 eggs per batch in moist areas. The eggs need to dry out before they can hatch into larvae. The eggs survive in the dry soil, in cracks and crevasses. Once the rain from storms begins, the areas become inundated with water, and the eggs are able to hatch. Florida floodwater mosquito species include Culex nigripalpus, Ochlerotatus taeniorhyncus, and Psorophora columbiae. Seal up cracks and holes in windows and doors, anything that may let a mosquito in. If you have a patio that is not enclosed, use mosquito netting. It is recommended that you use a sturdy net and contain 156 holes per square inch at a minimum. Frogs, birds, dragonflies, and certain kinds of fish all eat mosquitoes. Attract birds by putting up a bird feeder or introduce beneficial bugs into your garden to help keep mosquitoes away. You won’t get every mosquito, but it may help in cutting down the numbers.

What can you do to stop mosquito breeding in your yard?

Mosquitos only need 1-2 centimeters of stagnant water to breed.

1. Change water in birdbaths 2x/week.

2. Be sure flower pots and the dish underneath does not contain standing water.

3. Be sure gutters are debris-free, so water will not collect in a leaf “dam.”

4. Bromeliads are a perfect habitat for mosquitos to develop. Flush bromeliads with a garden hose 2x/week.

5. Check yard toys and yard ornaments for standing water.

6. Check for leaks from outdoor faucets and around your air conditioner.

7. Is there standing water in your boat or any other vehicle stored outdoors?

8. Look for standing water near your swimming pool, pool equipment, and pool toys.

9. Check for standing water in holes in trees and bamboo.

10. Walk around and look for water in things like trash cans, trash can lids, and any container or object where water can accumulate.

—— Install a Bat House ——–

Bats can eat up to 600 mosquitos in an hour!!

Shield-Backed Bug

This little guy is a Shield-backed Bug (Orsilochides guttata). The shield-backed bugs are related to the stink bugs and are true bugs, unlike the beetles they closely resemble. Like other true bugs, shield-backed bugs go through several stages of development (instars) of nymphs until they reach adulthood.

They feed on plants, including many commercial crops.

There are hundreds of shield-backed bug species ranging in color from rather drab to bright metallic greens and reds. Like stink bugs, when disturbed, shield-backed bugs will emit an odor to deter predators.

This little bug is perched on a goldenrod flower in late September in the Lower Wekiva Preserve State Park in Seminole County, Florida

Palmetto Tortoise Beetle Larva

These little Palmetto Tortoise Bettle Larva undergo metamorphosis. They start as a segmented cluster of eggs that look like a tangled mess. They then enter the larval stage, progress to a pupal stage, and then become adults. During the pupal stage, they create an umbrella out of dead cells and feces. It’s held on by what is called anal forks. These beetles also create an oil that helps them suction to leaves with force up to 60 times its own weight. This prevents most predators except the wheel bug from eating them.

The Milkweed Assassin

The Milkweed Assassin (Zelus longipes ) might sound like a villain but think of him as a vigilante for your garden. They are fantastic at catching invasive or hard-to-manage insects that would otherwise damage your garden. These funny little bugs set a sticky chemical trap before hiding in the foliage. Once they catch their prey, they use a long feeding appendage referred to as a beak, which is used to suck the fluids out of their prey. They will eat almost any type of flies, aphids, and broom moths. If you see them in your garden, don’t be alarmed. They are there to help. Just don’t touch them. Their bite can leave a burning sensation that swells for a few days.

https://www.facebook.com/imagineourflorida/videos/1866477470270770/

Recent Comments