Wetlands – Definition and Description

Scrubs

Scrubs are the remains of an archipelago that existed over 25 million years ago (Bostick, et al. 2005). Today, these ecosystems are characterized by low-quality sandy soil and are dominated by sand pines. The primary soil type is entisol which allows water to drain well and replenish the aquifer (The Nature Conservancy 1991). Plant species within the area are fire-adapted (Abrahamson, 1984).

Fire regiments are typically every 20 to 80 years and are facilitated by resin from sand pines, which are highly flammable (Menges and Kohfeldt, 1995). As a result, a fire rapidly spreads through the system and climbs to the treetops, creating what is referred to as “crown fires.” The heat from these fires facilitates a serotinous response, opening of sand pinecones. This heat is necessary for the release of seeds (Brendemuehl, 1990). Following fire regiments, a large and diverse collection of seeds are dispersed to the understory and can remain dormant for several years (Carrington ME, 1997).

Most sand pine scrub fires occur between February and June, with approximately 80% occurring during this time (Cooper, 1973). Historically, the primary means of fire ignition was lightning (Komarek, 1964.) Now, management practices include prescribed burns and mechanical harvesting of pines, which are recommended between March and May (Main and Menges, 1997).

Conservation efforts are necessary to maintain a healthy habitat for wildlife and to prevent extinctions, but there are other values that make conservation of these areas so important. Scrubs produce a relatively small economic value, but it is important that practices for harvesting sand pines are sustainable.

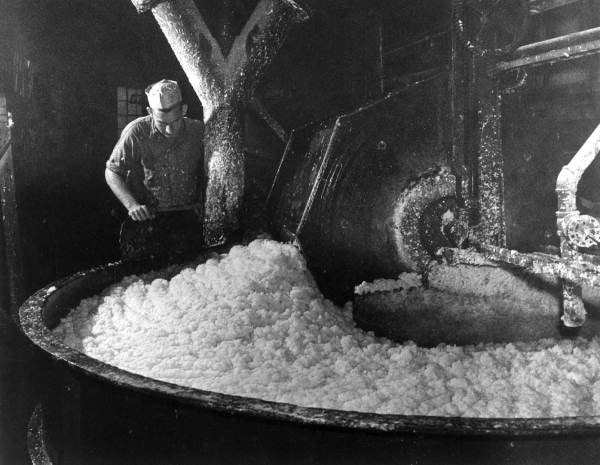

One sector that has been working on best management practices for sustainable use is the timber industry. An average of 40,000 acres a year of timber is produced from scrubs (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012). Sand pines are mostly used for wood pulp. To produce sufficient pulp, the trees need to be at least 35 years old. Alternative growth rotations are necessary to ensure a sustainable harvest that has led to a cost-effective strategy of preparing the ground for seeding. This strategy includes clear-cutting, roller chopping, seeding, and 35 years of growth (Hinchee and Garcia, 2017).

Photo: Pine pulp at a paper mill in Pensacola 1947.

References:

Abrahamson W. 1984. Species responses to fire on the Florida lake wales ridge. American Journal of Botany 71.

Bostick, K. Johnson SA, and Main MB. 2005. Florida geological history. UF/IFAS Extension.

Brendemuehl R.H. 1990. Pinus clausa (Chapm. ex Engelm.) Vasey ex Sarg., Sand Pine. Silvics of North America 1:294-301.

Carrington ME. 1997. Soil seed bank structure and composition in Florida sand pine. American Midland Naturalist 137(1).

Cooper, R.W. 1973. Fire and sand pine. Sand pine symposium proceedings. General technical report SE-2. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service; Marianna, Florida. 207

Hinchee J and Garcia JO. 2017. Sand Pine and Florida Scrub-Jays—An Example of Integrated Adaptive Management in a Rare Ecosystem. Journal of Forestry 115:230-237

Komarek EV Sr. 1964. The natural history of lightning. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers fire ecology conference 8. Tall Timbers Research Station; Tallahassee, Florida.

The Nature Conservancy, Archbold Biological Station, Florida Natural Areas Inventory. 1991. Lake Wales/Highlands Ridge Ecosystem CARL Project Proposal, January 1991.

Longleaf Pine

The Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) gets its name from the shape of its needle-like leaves. They can grow up to18 inches long and come in bundles of three. The tree with its thick, scaly bark grows almost completely straight, boasts a 3-foot diameter, and can reach 80 to 100 feet tall. These slow-growing trees can live up to 300 years.

Prior to restoration efforts, longleaf pines only occupied 3% of their former range. Forests of longleaf pine were cleared for development and agriculture.

Longleaf pine seeds are developed in cones and dispersed by the wind. They must find their way to soil to take root and grow. Fires caused by lightning would naturally clear away leaf litter and brush allowing this to take place. When the fire is suppressed, the seeds cannot reach the soil.

Once the seeds take root, they go through a grass stage. During this stage, the Longleaf pine starts to develop its central root, called a taproot, which will grow up to 12 feet long. Once the taproot is firmly in the earth, the tree will begin to grow in height. Both the tree and the grass stage are resistant to fire.

There are more than 30 endangered and threatened species, including red-cockaded woodpeckers and indigo snakes who rely on the longleaf pine habitat. Longleaf pines are more resilient to the negative impacts of climate change than other pines. The tree can withstand severe windstorms, resist pests, tolerate wildfires and drought, as well as capture carbon pollution from the atmosphere. Restoration of Longleaf pine forests has become a major effort in Florida and gives us a renewed hope that these ecosystems and all who live there will thrive once again.

Coral Reef

—-Coral Reef—-

Florida is the only state in the continental United States with a shallow coral reef near its coast. Coral reefs create specialized habitats that provide shelter, food, and breeding sites for numerous plants and animals.

Recent Comments